Issue 95, Spring 1985

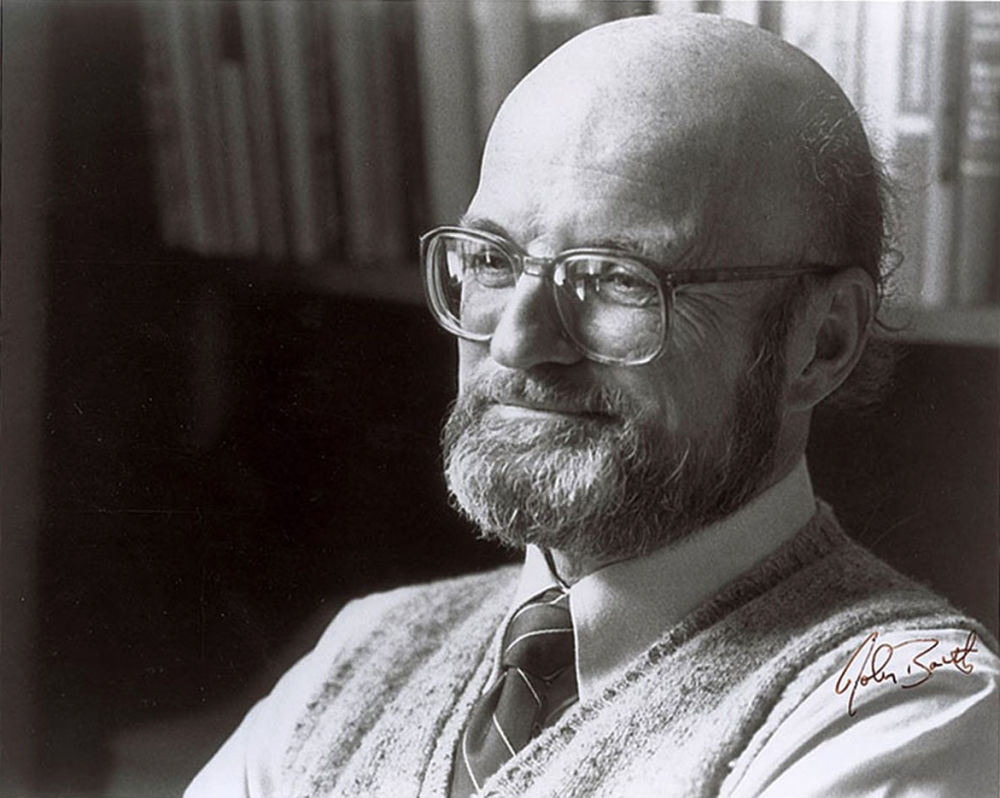

This interview with John Barth was conducted in the studios of KUHT in Houston, Texas, for a series entitled The Writer in Society. The stage set was made up to resemble a writer’s den—the decor including a small globe of the world, bronze Remington-like animal statuary, a stand-up bookshelf with glass shelves on which were placed some potted plants and a haphazard collection of books, a few volumes of the Reader’s Digest condensed novel series among them. Large pots of plants were set about. Barth sat amongst them in a cane chair. He is a tall man with a domed forehead; a pair of very large-rimmed spectacles give him a professorial, owlish look. He is a caricaturist’s delight. He sports a very wide and straight mustache. Recently he had grown a beard. In manner, Barth has been described as a combination of British officer and Southern gentleman.

“We’ll have to stick to the channel,” he wrote in his first novel, The Floating Opera, “and let the creeks and coves go by.” Every novel since then has been a refutation of this dictum of sticking to the main topic. He is especially influenced by the classical cyclical tales such as Burton’s Thousand and One Nights and the Gesta Romanorum, and by the complexities of such modern masters as Nabokov, Borges, and Beckett. For novels distinguished by a wide range of erudition, invention, wit, historical references, whimsy, bawdiness, and a great richness of image and style, Barth has been described as an “ecologist of information.”

Of his working habits Barth has said that he rises at six in the morning and puts an electric percolator in the kitchen so that during the course of sitting for six hours at his desk he has an excuse for the exercise of walking back and forth from his study to the kitchen for a cup of coffee. He speaks of measuring his work not by the day (as Hemingway did) but by the month and the year. “That way you don’t feel so terrible if you put in three days straight without turning up much of anything. You don’t feel blocked.”

This interview, being restricted to a half-hour’s conversation for a television audience, was thought to be a bit short by the usual standards of the magazine. It was assumed that Barth, being such a master of the prolix, would surely make some additions. Extra questions were sent him. The interview was returned to these offices with the questions unanswered, and the text of the interview edited and shortened. Perhaps Barth had not noticed the additional questions. This interview was sent back, this time with a small emolument attached for taking the trouble. The interview was returned once again, along with the uncashed check, with the following statement: “It doesn’t displease me to hear that our interview will be perhaps the shortest one you’ve run. In fact, it’s a bit shorter now than it was before (enclosed). Better not run it by me again!”

INTERVIEWER

When were the first stirrings? When did you actually understand that writing was going to be your profession? Was there a moment?

JOHN BARTH

It seems to happen later in the lives of American writers than Europeans. American boys and girls don’t grow up thinking, “I’m going to be a writer,” the way we’re told Flaubert did; at about age twelve he decided he would be a great French writer and, by George, he turned out to be one. Writers in this country, particularly novelists, are likely to come to the medium through some back door. Nearly every writer I know was going to be something else, and then found himself writing by a kind of passionate default. In my case, I was going to be a musician. Then I found out that while I had an amateur’s flair, I did not have preprofessional talent. So I went on to Johns Hopkins University to find something else to do. There I found myself writing stories—making all the mistakes that new writers usually make. After I had written about a novel’s worth of bad pages, I understood that while I was not doing it well, that was the thing I was going to do. I don’t remember that realization coming as a swoop of insight, or as an exhilarating experience, but as a kind of absolute recognition that for well or for ill, that was the way I was going to spend my life. I had the advantage at Johns Hopkins of a splendid old Spanish poet-teacher, with whom I read Don Quixote. I can’t remember a thing he said about Don Quixote, but old Pedro Salinas, now dead, a refugee from Franco’s Spain, embodied to my innocent, ingenuous eyes, the possibility that a life devoted to the making of sentences and the telling of stories can be dignified and noble. Whether the works have turned out to be dignified and noble is another question, but I think that my experience is not uncommon: You decide to be a violinist, you decide to be a sculptor or a painter, but you find yourself being a novelist.

INTERVIEWER

What was the musical instrument you started out with?

BARTH

I played drums. What I hoped to be eventually was an orchestrator—what in those days was called an arranger. An arranger is a chap who takes someone else’s melody and turns it to his purpose. For better or worse, my career as a novelist has been that of an arranger. My imagination is most at ease with an old literary convention like the epistolary novel, or a classical myth—received melody lines, so to speak, which I then reorchestrate to my purpose.

INTERVIEWER

What’s first when you sit down to begin a novel? Is it the form, as in the epistolary novel, or character, or plot?

BARTH

Different books start in different ways. I sometimes wish that I were the kind of writer who begins with a passionate interest in a character and then, as I’ve heard other writers say, just gives that character elbowroom and sees what he or she wants to do. I’m not that kind of writer. Much more often I start with a shape or form, maybe an image. The floating showboat, for example, which became the central image in The Floating Opera, was a photograph of an actual showboat I remember seeing as a child. It happened to be named Captain Adams’ Original Unparalleled Floating Opera, and when nature, in her heavy-handed way, gives you an image like that, the only honorable thing to do is to make a novel out of it. This may not be the most elevated of approaches. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, for example, comes to the medium of fiction with a high moral purpose; he wants, literally, to try to change the world through the medium of the novel. I honor and admire that intention, but just as often a great writer will come to his novel with a much less elevated purpose than wanting to undermine the Soviet government. Henry James wanted to write a book in the shape of an hourglass. Flaubert wanted to write a novel about nothing. What I’ve learned is that the muses’ decision to sing or not to sing is not based on the elevation of your moral purpose—they will sing or not regardless.

INTERVIEWER

What was in your way that you had to get out of your way?

BARTH

What was in my way? Chekhov makes a remark to his brother, the brother he was always hectoring in letters, “What the aristocrats take for granted, we pay for with our youth.” I had to pay my tuition in literature that way. I came from a fairly unsophisticated family from the rural, southern Eastern Shore of Maryland—which is very “deep South” in its ethos. I went to a mediocre public high school (which I enjoyed), fell into a good university on a scholarship, and then had to learn, from scratch, that civilization existed, that literature had been going on. That kind of innocence is the reverse of the exquisite sophistication with which a writer like Vladimir Nabokov comes to the medium—knowing it already, as if he’s been in on the conversation since it began. Yet the innocence that writers like myself have to overcome, if it doesn’t ruin us altogether, can become a sort of strength. You’re not intimidated by your distinguished predecessors, the great literary dead. You have a chutzpah in your approach to the medium that may carry you through those apprentice days when nobody’s telling you you’re any good because you aren’t yet. Everything is a discovery. I read Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn when I was about twenty-five. If I had read it when I was nineteen, I might have been intimidated; the same with Dickens and other great novelists. In my position I remained armed with a kind of “invincible innocence”—I think that’s what the Catholics call it—that with the best of fortune can survive even later experience and sophistication and carry you right to the end of the story.

INTERVIEWER

What were the particular guides that helped you?

BARTH

The great guides were the books I discovered in the Johns Hopkins library, where my student job was to file books away. One was more or less encouraged to take a cart of books and go back into the stacks and not come out for seven or eight hours. So I read what I was filing. My great teachers (the best thing that can happen to a writer) were Scheherazade, Homer, Virgil, and Boccaccio; also the great Sanskrit tale-tellers. I was impressed forever with the width as well as the depth of literature—just what a kid from the sticks, from the swamp, in my case, needed. As an undergraduate I had a couple of tutors in writing who were not themselves writers. They were simply good coaches. I’ve thought of that in a chastened way since. Dealing with my own students, many of whom are very skillful, advanced apprentice writers, I often wonder whether it’s a good idea for them to have, at the other end of the table, somebody who’s already working at a certain level of success and notoriety. Is that not perhaps intimidating? I just don’t know, but I suspect the trade-off is fair enough. I might have learned some things faster had I been working with an established writer rather than a very sympathetic coach.

INTERVIEWER

In browsing through the libraries, was it the concept of simply telling stories that fascinated you, or was it the characters that came through the works you read? What was it that struck the spark?

BARTH

It was not the characters. Perhaps I would be a better novelist in the realm of characterization had it been. No, it was the mere mass of the narrative. My apprenticeship was a kind of Baptist total immersion in “the ocean of rivers of stories”—that’s the name of one of those old Sanskrit jobs that I read in my filing days . . . one volume at a time up to volume seventeen. I think the sweetest kind of apprenticeship that a narrative artist can serve is that sort of immersion in the waters of narrative, where by a kind of osmosis you pick up early what a talented writer usually learns last: the management of narrative pace, keeping the story going.

INTERVIEWER

I noticed you call it coaching rather than teaching. I don’t think I’ve ever heard that phrase used to describe that relationship.

BARTH

Coaching is more accurate. God knows whether we should be doing it in the universities at all. I happen to think there’s some justification for having courses in so-called creative writing. I know from happy experience with young writers that the muses make no distinction between undergraduates and graduate students. The muses know only expert writers and less expert writers. A beginner—such as I was when, with the swamp still on my shoes, I came into Johns Hopkins as an undergraduate—needs to be taught that literature is there; here are some examples of it, and here’s how the great writers do it. That’s teaching. In time, a writer, or any artist, stops making mistakes on a crude, first level, and begins making mistakes on the next, more elevated level. And then finally you begin to make your mistakes on the highest level—let’s say the upper slopes of slippery Parnassus—and it’s at that point you need coaching. Now sometimes coaching means advising the skier to come down off the advanced slope and back to the bunny hill for a while, back to the snowplow. One must be gentle about it. To shift metaphors violently, one must understand that the house of fiction has many windows; you don’t want to defenestrate your young apprentices. But sometimes such a simple thing as suggesting to a student that perhaps realism instead of fantasy may be a more sympathetic genre, or humor instead of the opposite, or the novel rather than the short story—sometimes a simple suggestion like that can be the one that makes things click. It doesn’t always.

INTERVIEWER

How confident are you in the house of fiction, or on the upper slopes, as you were putting it?

BARTH

About my own position on the giant slalom of the muses?

INTERVIEWER

I don’t mean in the eyes of others, but in your own sense of what you’re up to.

BARTH

It’s a combination of an almost obscene self-confidence and an ongoing terror. You remember the old story of how Hemingway would always record the number of words he wrote each day. When I learned that detail about Hemingway I understood why the poor chap went bonkers and did himself in at the end. The average professional, whether he’s good or mediocre, learns enough confidence in himself so that he no longer fears the blank page. About my own fiction: my friend John Hawkes once said of it that it seems spun out against nothingness, simply so that there should not be silence. I understand that. It’s Scheherazade’s terror: the terror that comes from the literal or metaphorical equating of telling stories with living, with life itself. I understand that metaphor to the marrow of my bones. For me there is always a sense that when this story ends maybe the whole world will end; I wonder whether the world’s really there when I’m not narrating it. Well, at this stage of my life I have enough confidence in myself to know that the page will fill up. Indeed, because I’m not a very consistent fiction writer (my books don’t resemble one another very much), I have an ongoing curiosity about what will happen next. Stendhal said that once when he wanted to commit suicide, he couldn’t abide to do it because he wanted to find out what would happen next in French politics. I have a similar curiosity . . . when this long project is over, what will fill the page next? I’ve never been able to think that far ahead; I can’t do it until the project in hand is out of the shop and going through the publisher’s presses. Then I begin to think about what will be next. I’m just as curious as the next chap. Maybe more so.

INTERVIEWER

How about in the middle of a book? Do you know in that case what’s going to be on the next page?

BARTH

There are writers who have the good fortune to be thinking three novels down the line or even to have two or three going at the same time. Not me.

INTERVIEWER

No, I mean within the same book. Do you know what the last line of the book might be when you start?

BARTH

I have a pretty good sense of where the book is going to go. By temperament I am an incorrigible formalist, not inclined to embark on a project without knowing where I’m going. It takes me about four years to write a novel. To embark on such a project without some idea of what the landfall and the estimated time of arrival were would be rather alarming. But I have learned from experience that there are certain barriers that you cannot cross until you get to them; in a thing as long and complicated as a novel you may not even know the real shape of the obstacle until you heave in sight of it, much less how you’re going to get around it. I can see in my plans that there will be this enormous pothole to cross somewhere around the third chapter from the end; I’ll get out my little pocket calculator and estimate that the pothole will be reached about the second of July, 1986, let’s say, and then just trust to God and the muses that by the time I get there I’ll know how to get around it.

INTERVIEWER

These are climactic moments that you know you’re going to have to deal with?

BARTH

Yes, important moments that I know from my sense of dramaturgy will have to be dealt with: rifles that will have to be fired.

INTERVIEWER

Like the Marabar Caves in A Passage to India?

BARTH

Exactly. That’s a suspense in the process of writing which I’ve learned to be both charmed and—faintly, decently—terrified by.

INTERVIEWER

Can you work around and then come back to deal with these climactic moments later?

BARTH

You come to it. Then it’s there. Early in the planning of Sabbatical, I knew that in the next-to-last chapter, when the characters sail their boat around a certain point, something extraordinary had to happen, something literally marvelous, but I had no idea what that ought to be until they actually did turn that corner. By then the metaphor was clear enough so that the sea monster, which had to surface at that moment, surfaced in my imagination just when it surfaced in the novel.

INTERVIEWER

When you start on a day’s work, do you reread for a while, up to where you stopped the day before?

BARTH

Sure. It’s to get the rhythm partly, and partly it’s a kind of magic: it feels like you’re writing, though you’re not. The processes get going; the wheels start spinning. I write in longhand. My Baltimore neighbor Anne Tyler and I are maybe the only two writers left who actually write with a fountain pen. She made the remark that there’s something about the muscular movement of putting down script on the paper that gets her imagination back in the track where it was. I feel that too, very much so. My sentences in print, as in conversation, tend to go on a while before they stop: I trace that to the cursiveness of the pen. The idea of typing out first drafts, where each letter is physically separated by a little space from the next letter, I find a paralyzing notion. Good old script, which connects this letter to that, and this line to that—well, that’s how good plots work, right? When this loops around and connects to that . . .

INTERVIEWER

Do you think word processors will change the style of writers to come?

BARTH

They may very well. But I remember a colleague of mine at Johns Hopkins, Professor Hugh Kenner, remarking that literature changed when writers began to compose on the typewriter. I raised my hand and said, “Professor Kenner, I still write with a fountain pen.” And he said, “Never mind. You are breathing the air of literature that’s been written on the typewriter.” So I suppose that my fiction will be word-processed by association, though I myself will not become a green-screener.

INTERVIEWER

Somewhere in Lost in the Funhouse, you berate the reader for reading . . .

BARTH

A dangerous thing to do.

INTERVIEWER

. . . and say that he should be staring at the wall or whatever. Is that something you believe or were you simply having fun?

BARTH

That was the mood of the character in that story, “Life-Story,” which also, in my mind, corresponded to an apocalyptic mood in our country at that time: the height of the sixties, when our republic enjoyed a more than usually apocalyptic ambience. A similar sort of apocalyptic feeling was going around about the future of print generally, and the novel in particular. I don’t feel strongly about the matter myself. The point of a couple of essays I’ve written, and some of the stories, is that the death of a genre is not the death of storytelling; storytelling is older than the form of the novel. I must say, though, that my sense of priorities about these matters has changed. In The Floating Opera, that first, very youthful novel of mine, the hero, who’s a man my present age (he’s in his early fifties), has a particular heart condition that has led him to lead his life wondering, as he moves from sentence to sentence, whether he’ll get from the subject to the verb, the verb to the object. The characters in the novel I’m working on now—a little like the characters in the last novel, Sabbatical—are much more concerned about whether the world will last, never mind the novel. Joyce Carol Oates once said she doesn’t like “Pop Apocalypses.” Though I like that phrase, I find the question of the literal persistence of civilization, in this powder keg we’re living in, a much more considerable question than the very trifling matter of whether a particular literary form is kaput, or dies for another two hundred years as happily as it’s been dying for the last two hundred.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think that the novelist can have any effect on this portentous thing you’re talking about?

BARTH

I don’t think that as a group we’d be any better at running the world than the people who are botching it up. Poetry makes nothing happen. Politically committed artists like Gabriel García Márquez give honest voice to their political passion at no great cost to the quality control of their art. But do they really change the world? I doubt it, I doubt it, Abraham Lincoln’s remark to Harriet Beecher Stowe notwithstanding: “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war!” Well, she didn’t. No. Without sounding too terribly decadent about it, I much prefer the late Vladimir Nabokov’s remark about what he wanted from his novels: “aesthetic bliss.” Well, that does sound too decadent. Let me change masters for a moment and say that I prefer Henry James’s remark that the first obligation of the writer—which I would also regard as his last obligation—is to be interesting, to be interesting. To be interesting in one beautiful sentence after another. To be interesting; not to change the world.

INTERVIEWER

I’ve always liked that exchange between William Gass and John Gardner in which Gardner said he wanted everyone to love his books and Gass replied that he wouldn’t want everyone to love his books any more than he would want everyone to love his sister or his daughter. Which side do you come down on?

BARTH

Gass accused the late Mr. Gardner with confusing love and promiscuity, which are not the same thing. Well, I am congenitally and temperamentally a novelist. The novel has its roots, very honorably, in the pop culture. The art novel notwithstanding, I think most of us novelists have a sneaking wish that we could have it both ways, as Charles Dickens did and as Gabriel García Márquez sort of does—to write novels that are both shatteringly beautiful and at the same time popular. Not to make a lot of money, but so that you can reach out and touch the hearts—no, that sounds hokey, doesn’t it? But it is what most novelists wish they could do—reach out a little bit beyond that audience of professional readers, those really devoted followers of contemporary fiction. That’s a navigational star that I confess I steer by. But I am, in fact, an amateur sailor and therefore an amateur navigator; I don’t confuse my navigational stars with my destination. No novel of mine has had that kind of popularity, and I don’t expect any novel of mine ever shall. But it’s a good piece of fortune when it happens. I think of the novel as being an essentially American genre in this way—I’m not talking about American novels, but American in a metaphorical sense: hospitable to immigrants and amateurs. My favorite literature is both of stunning literary quality and democratic of access. This is not to mean I have a secret wish to be my Chesapeake neighbor, James Michener.

INTERVIEWER

Would you ever make a compromise in your books to gain more readers?

BARTH

I would, but I can’t. I start every new project saying, “This one’s going to be simple, this one’s going to be simple.” It never turns out to be. My imagination evidently delights in complexity for its own sake. Much of life, after all, and much of what we admire is essentially complex. For a temperament such as mine, the hardest job in the world—the most complicated task in the world—is to become simpler. There are writers whose gift is to make terribly complicated things simple. But I know my gift is the reverse: to take relatively simple things and complicate them to the point of madness. But there you are: one learns who one is, and it is at one’s peril that one attempts to become someone else.

INTERVIEWER

Do your children enjoy your books?

BARTH

I have no idea whether those rascals read them. I think they sneaked them when they were teenagers, but they’ve grown up to be scientists and business types. I think they’re happy that their daddy writes things that have a certain heft. But do they read them? I don’t know. When we finish our conversation I’ll call them up one at a time and ask them.

Author photograph by Nancy Crampton.